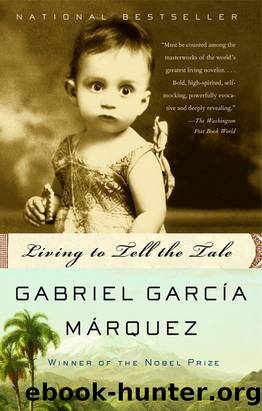

Living to Tell the Tale by Gabriel García Márquez

Author:Gabriel García Márquez [Marquez, Gabriel Garcia]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 978-1-101-91115-0

Publisher: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group

Published: 2014-10-01T00:00:00+00:00

In spite of his right-wing sympathies and personal friendship with Laureano Gómez, Carranza highlighted the sonnets in his literary pages, more as a journalistic scoop than a political proclamation. But the negative response was almost unanimous. Above all because of the illogicality of publishing them in the paper of a dyed-in-the-wool liberal like the former president Eduardo Santos, who was as opposed to the retrograde thought of Laureano Gómez as he was to Pablo Nerudaâs revolutionary ideas. The noisiest reaction came from those who could not tolerate a foreigner permitting himself that kind of abuse. The mere fact that three casuistic sonnets, more ingenious than poetic, could set off such a storm was a heartening symptom of the power of poetry during those years. In any event, Laureano Gómez himself, who was then president of the Republic, later prohibited Neruda from entering Colombia, as did General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla in his day, but he was in Cartagena and Buenaventura, ports of call for the steamships between Chile and Europe, on several occasions. For the Colombian friends to whom he announced his visit, each stopover on the round trip was a reason for stupendous celebration.

When I enrolled in the faculty of law in February 1947, my identification with the Stone and Sky group remained unshaken. Although I had met its most notable members in Carlos MartÃnâs house in Zipaquirá, I did not have the audacity to remind even Carranza of that, and he was the most approachable. On one occasion I happened to see him in the LibrerÃa Grancolombia, so close to me and so accessible that I greeted him as an admirer. His response was very cordial but he did not recognize me. On the other hand, on another occasion, Maestro León de Greiff got up from his table at El Molino and greeted me at mine when someone told him I had published stories in El Espectador, and he promised to read them. Sad to say, a few weeks later the popular uprising of April 9 took place, and I had to leave the still-smoking city. When I returned after four years, El Molino had disappeared under its ashes, and the maestro had moved with all his household goods and his court of friends to the café El Automático, where we became friends of books and aguardiente, and he taught me to move chessmen without art or good fortune.

My friends from an earlier time found it incomprehensible that I would persist in writing stories, and even I could not explain it in a country where the greatest art was poetry. I learned this when I was very young through the success of âMiseria humana,â a popular poem sold in folded sheets of coarse wrapping paper or recited for two centavos in the markets and cemeteries of Caribbean towns. The novel, on the other hand, was limited. After MarÃa, by Jorge Isaacs, many had been written with no great resonance. José MarÃa Vargas Vila had been an unusual phenomenon with his fifty-two novels aimed at the heart of the poor.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| African | Asian |

| Australia & Oceania | Canadian |

| Caribbean & Latin American | European |

| Jewish | Middle Eastern |

| Russian |

The Hating Game by Sally Thorne(17506)

The Universe of Us by Lang Leav(14382)

Sad Girls by Lang Leav(13363)

The Lover by Duras Marguerite(7133)

Smoke & Mirrors by Michael Faudet(5520)

The Rosie Project by Graeme Simsion(5201)

The Shadow Of The Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón(4949)

Big Little Lies by Liane Moriarty(4892)

The Poppy War by R. F. Kuang(4457)

Memories by Lang Leav(4179)

What Alice Forgot by Liane Moriarty(3929)

An Echo of Things to Come by James Islington(3852)

From Sand and Ash by Amy Harmon(3695)

The Poetry of Pablo Neruda by Pablo Neruda(3372)

The Tattooist of Auschwitz by Heather Morris(3262)

Guild Hunters Novels 1-4 by Nalini Singh(2940)

Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges(2874)

THE ONE YOU CANNOT HAVE by Shenoy Preeti(2830)

The Rosie Effect by Graeme Simsion(2716)